A week to face hard truths and build compassionate support

Black Baby Loss Awareness Week, marked from 12–18 May 2025, brings needed attention to a reality too often left in the shadows. It focuses on the lives, grief, and systemic injustices faced by Black families in the UK who experience miscarriage, stillbirth, and neonatal death. For many, this week is about honouring children who are no longer here, while demanding that healthcare services do better.

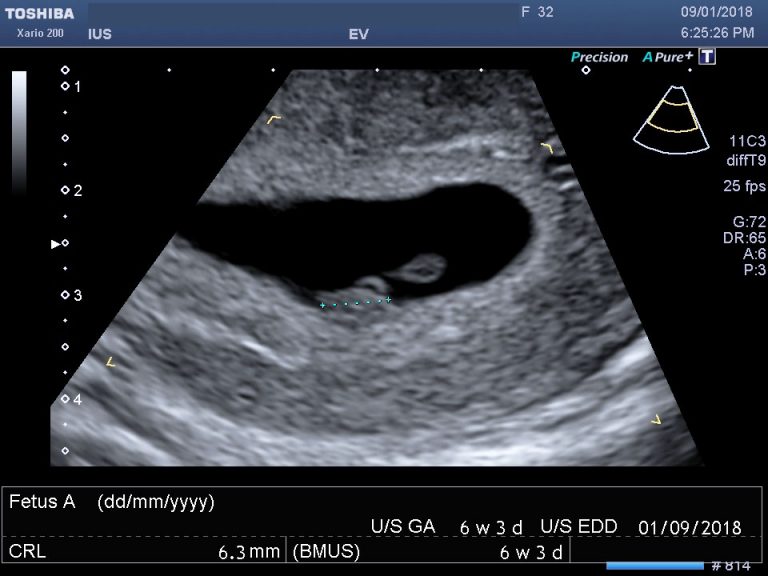

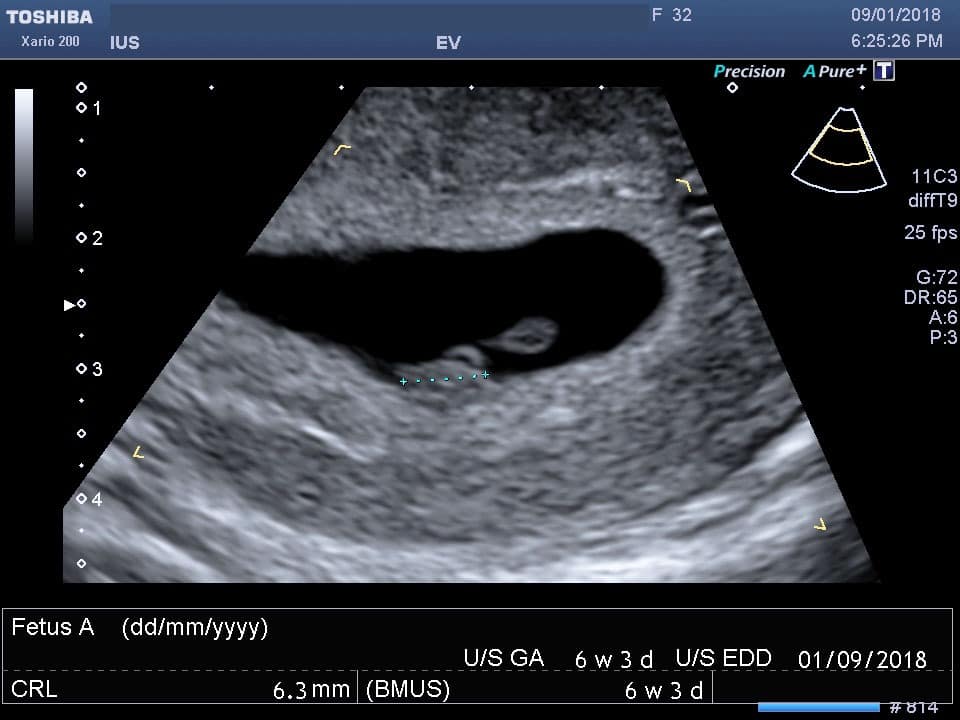

At IUS London, this issue is close to our daily work. We see the hopes that come with early pregnancy and understand the anxiety that follows loss. Every scan we perform holds layers of emotion—especially for those already carrying pain. This week, we reflect openly on the disparities, the stories behind them, and how ultrasound services can support safe and compassionate care for all.

The reality in the UK: not everyone’s risks are equal

Data from MBRRACE-UK (Mothers and Babies: Reducing Risk through Audits and Confidential Enquiries across the UK) has shown consistent racial disparities in pregnancy loss outcomes. Between 2013 and 2018, overall perinatal mortality rates fell by 15%, yet babies born to Black and Asian families remained at significantly higher risk of dying before or shortly after birth. These deaths were not random—they were patterned, persistent, and preventable in many cases. The report also highlighted that mothers living in the most deprived areas, which includes a disproportionate number of Black families, faced the worst outcomes (BMJ, Elisabeth Mahase, 2020).

In the most extensive analysis to date, a meta-study of over 2 million pregnancies published in The Lancet revealed that babies born to Black women in high-income countries were twice as likely to be stillborn compared to those born to White women. The odds of neonatal death were also twice as high. Risks of preterm birth and being born small for gestational age were substantially greater. These patterns held true across multiple countries, regardless of healthcare system or region, pointing to deeper structural issues (Sheikh et al., The Lancet, 2022).

Why the disparity persists

Medical risk factors alone cannot explain this. Studies have repeatedly shown that Black women of all socioeconomic levels, including those with higher education and no underlying health conditions, still face worse outcomes. According to American Journal of Epidemiology, one major study found that interpersonal and environmental stressors—financial strain, trauma, emotional upheaval, and unstable relationships—are all more likely to be experienced by Black women, and these significantly increase the risk of stillbirth (Hogue et al., 2013).

Racism is a factor that cannot be overlooked. Research in the Journal of Black Psychology documented that African American women consistently described not being listened to by care providers, feeling dismissed, and lacking access to respectful emotional support at the time of loss. They experienced not only the grief of losing a baby but the added weight of navigating care systems where they were not believed or understood (Evans et al., 2022).

The African American Women’s Heart & Health Study also found that experiences of racism throughout life—direct or vicarious—significantly increased miscarriage risk. The physiological toll of long-term stress, often described as "weathering," is linked to poorer reproductive health outcomes (Daniels, 2016).

Listening matters: stories show the gaps in care

Behind the statistics are real families, many of whom feel their pain was not fully acknowledged. A qualitative study published in BMJ Open involving women who lost babies between 20 and 28 weeks gestation, highlighted the emotional intensity of those early losses. Even when medical professionals tried to reassure patients with phrases like “it’s early” or “these things happen,” the message often missed the depth of grief being felt. Many mothers said they didn’t just lose a pregnancy—they lost a child, and they wanted that loss recognised (Heazell et al., 2024).

This disconnect is magnified for Black women. A publication in The Practising Midwife explored why many Black women mistrust maternity services. The reasons were not vague. Many spoke of being ignored when raising concerns, having symptoms brushed off, and not receiving the same level of monitoring or care as White women. These experiences build a lasting wariness and affect how safe people feel in medical settings (Horn, 2020).

Early scans play a quiet but powerful role

Early pregnancy scans can be a moment of reassurance—or the first sign that something is wrong. They’re not just diagnostic tools. They’re also moments of emotional significance for parents, especially those who have experienced loss before.

At IUS London, we regularly support people who arrive carrying anxiety from previous losses. Early pregnancy and viability scans offer a clear picture of gestational development. They can help identify concerns early, such as ectopic pregnancy, missed miscarriage, or problems with fetal growth. In many cases, timely detection allows for better clinical support.

Private clinics like ours provide an added layer of access when patients feel rushed or unheard in NHS settings. We take time. We listen. We recognise that early scans are not routine for every parent—sometimes they are carried out after days of bleeding or gut feelings that something isn’t right.

These moments must be treated with sensitivity. For someone who’s lost a baby before, an ultrasound appointment is not “just a check-in.” It’s often a quiet test of hope.

Improving care means seeing the full picture

In 2022, a team led by Thilaganathan and colleagues showed that targeted screening programmes using predictive models for preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction led to significant reductions in adverse outcomes—especially among Black and minority ethnic women. Their study in BJOG reported a threefold reduction in perinatal deaths among these groups, compared to no change in White women. These findings suggest that when care is proactive and personalised, outcomes can change dramatically (Liu et al., 2022).

This goes beyond algorithms and screenings. It means making space for patients’ voices. It means acknowledging the weight of previous trauma. It means building healthcare settings where Black women feel seen and heard.

We all have a role in changing this

This awareness week is not just about mourning. It’s also about responsibility. Clinics, charities, and healthcare professionals each have a role to play. So do policymakers, researchers, and educators.

Groups like Five X More, Tommy’s, and Sands are leading national efforts to reduce inequalities in baby loss and improve support. Their work includes education campaigns, advocacy, and culturally relevant grief resources. But support can start in smaller places too—in clinics, scan rooms, and every conversation that holds space for someone’s grief without rushing to fix it.

At IUS London, our team includes sonographers and healthcare professionals who understand the emotional stakes of early pregnancy. Our scan rooms are designed for calm. Our approach is quiet, thorough, and respectful. When loss has occurred, we make time for explanation, silence, and dignity. We don’t rush people out the door.

Support and resources

Whether you’ve experienced loss yourself or want to support someone who has, there are places to turn. Here are trusted UK-based resources offering grief counselling, peer support, and medical information:

Five X More – A grassroots campaign committed to improving maternal outcomes for Black women in the UK.

Website: www.fivexmore.comTommy’s – A research-driven charity focused on miscarriage, stillbirth, and premature birth.

Website: www.tommys.orgSands (Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Charity) – Provides support for bereaved families and works on bereavement training for professionals.

Website: www.sands.org.ukBirthrights – A UK charity that promotes respectful and informed maternity care.

Website: www.birthrights.org.uk

Content Information

We review all clinical content annually to ensure accuracy. If you notice any outdated information, please contact us at info@iuslondon.co.uk.

About the Author:

Yianni is a highly experienced sonographer with over 21 years in diagnostic imaging. He holds a Postgraduate Certificate in Medical Ultrasound from London South Bank University and is registered with the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC: RA38415). Currently working at Barts Health NHS Trust, Yianni specialises in abdominal, gynaecological, and obstetric ultrasound. He is a member of the British Medical Ultrasound Society (BMUS), Society of Radiographers (SoR) and regularly contributes to sonographer and junior radiologists training programs.